News

Can your technology choices create better online learning spaces?

Share with colleagues

Download the full Case Study

Take an in-depth look at how educators have used Cadmus to better deliver assessments.

In 2019, a national survey of provosts and vice-chancellors found that 83% of universities planned to increase their online programs and offerings. Even though online learning was on the radar of most universities, no one could have predicted the rapid adoption of remote teaching we saw in early 2020. As the pandemic forced the world to adapt like never before, every sector was impacted by drastic change. Perhaps though, the education sector was one of the hardest hit. As students returned home and teachers scrambled to move content online, most universities had to undergo their largest digital transformation to date.

Looking at technology changes last year, an ACODE whitepaper explored the exam and assessment solutions implemented by universities in Australia and New Zealand. It found that 51% of institutions adopted proctoring solutions (using dedicated platforms or Zoom), while the rest expanded the use of existing tools like the LMS, Turnitin, and even Cadmus.

With space now for thoughtful consideration, and a need to build resilient online learning spaces for the future, it is important for universities to take stock.

Were the technologies we adopted during the pandemic hasty decisions or lasting solutions to support student learning?

Two types of technologies

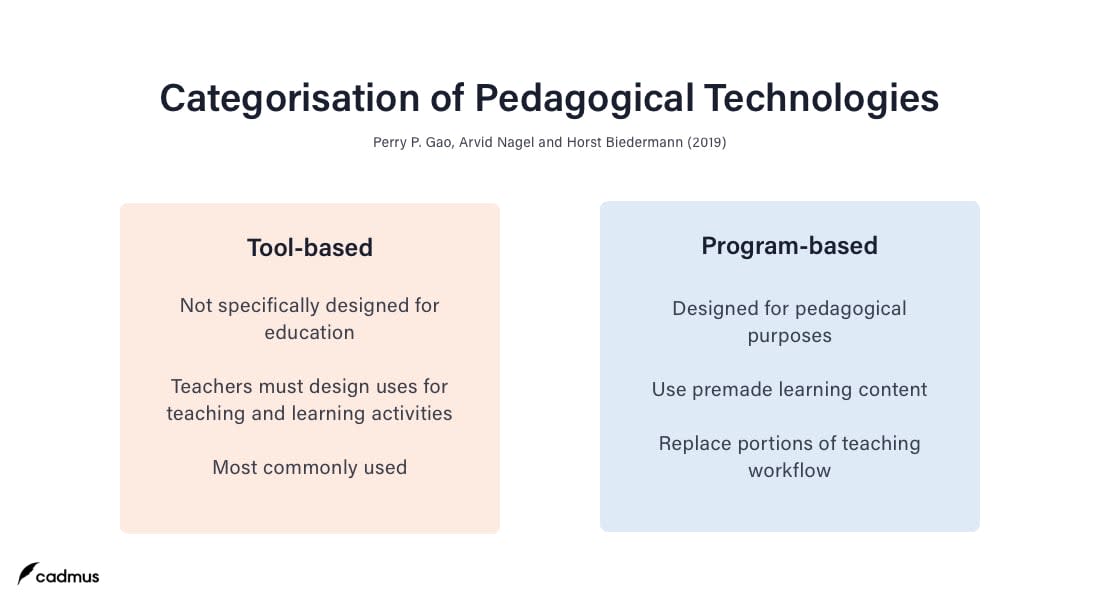

To understand what technologies are best suited for online learning, it's easiest to break down the different solutions available to institutions. Gao et al. (2019) provide a simple framework, categorising pedagogical technologies (any tool that supports the process of teaching and learning) into two distinct groups; tool-based technologies and program-based technologies.

An overview of the differences between tool-based and program-based technologies.

An overview of the differences between tool-based and program-based technologies.

Tool-based technologies were never explicitly designed for learning. Over the years, they have been co-opted by teachers to assist with parts of their workflow. Examples include Microsoft Word or PowerPoint, which are widely used by teachers to create learning materials or students to write submissions. However, the tools themselves do not help to improve teaching or learning in any way.

Platforms like ProctorU or similar proctoring tools can also be classed as tool-based technologies, replacing the in-person invigilation workflow without offering any learning benefits. These tools provide administrative benefits, but little else when it comes to teaching and learning.

On the other hand, program-based technologies are specifically designed for pedagogical purposes. They use pre-made learning content and focus on replacing considerable portions of a teacher's work, such as instruction delivery, feedback, or academic skills development. By focussing on the teaching and learning journey, these technologies guide teachers and students towards better outcomes.

Take applications like Cadmus or Duolingo — two great examples of program-based technologies. Although used in different contexts, at their core, they combine learning content and educative nudges to extend teaching beyond in-class interactions.

The right tool for the job

Over the last two years, almost all new technologies used by universities were tool-based (video conferencing, proctoring, content delivery solutions, and more). While this approach provided convenience during a stressful time, it's important to understand the long term impacts of adopting tool-based technologies at scale.

Without any pedagogical support in a product, pressure is placed on teachers to innovate and generate desired outcomes. This can be a significant challenge for time-poor educators. And with the success of wide-scale adoption entirely dependent on how teachers engage, this creates an increasing need for access to professional support. Paired with tight budgets, this can put successful tool adoption at risk.

In contrast, investing in program-based technologies, especially those co-designed with educational researchers and institutions, is more economically efficient. These tools offer a compelling path forward, providing students with more autonomy in the learning process and teachers more capacity to help students with higher-level learning. By taking the pressure off individual teachers and support staff, the right program-based tool can help universities scale up quality education and create supportive online learning spaces.

Category

Leadership

More News

Load more

Academic Integrity

Assessment Design

Teaching & Learning

Student Success

From bold ideas to real assessment change: What we heard at the Universities Australia Solutions Summit

Last week in Canberra, the Universities Australia Solutions Summit delivered on its promise of big ideas, bold conversations, and real solutions. These are the themes that stood out—from keynote sessions to candid conversations with university leaders across the Summit.

Cadmus

2026-03-02

Assessment Design

Company

Independent ROI analysis: What the findings mean for Universities

Independent analysis by Nous Group confirms a clear link: stronger assessment design improves student outcomes, strengthens retention, and delivers measurable financial return — with a 7.1x average ROI.

2026-02-18

Assessment Design

Leadership

Teaching & Learning

Secure assessment: From policy to practice

This article examines how Australian universities can translate assessment policy intent into sustainable practice amid growing pressures from generative AI, regulatory expectations, and equity considerations. It advocates a shift from surveillance-driven approaches toward a whole-of-institution, design-led model of academic integrity that balances secure assessment with learner-centred practice and public trust.

Cadmus

2026-02-09